By Colin Vanden Berg

In 1791, the Massachusetts Historical Society formed, sparking a tradition of preserving and showcasing local history which continues to this day in towns and cities across the country. In 2019, the Lancaster County Historical Society continues the tradition of preserving and presenting local history by opening a new exhibit titled, “Lancaster in the 1960s.” A closer look at the history of local historical societies in America and a visit to Lancaster Historical Society in fall 2019 thoroughly illustrates the important work they do for their communities.

American Historical Society co-founder John Franklin lists six main objectives of American Historical societies in his 1897 book “The Functions of State and Local Historical Societies.” According to Franklin, United States historical societies have six main functions: collecting/preserving historical materials such as printed manuscripts; maintaining well-cataloged libraries and museums, keeping the public engaged and informed, keeping alive “a patriotic regard for local history,” organizing events celebrating local history, accumulating biographical and obituary records, and finally, attracting money and members.

For context, most American historical societies follow the blueprint established by the Massachusetts Historical Society, which, according to historian Julian Boyd in the 1934 edition of “The Historical Review,” derived from the New Englanders’ clear understanding of how their history and heritage influenced their present situation.

Boyd explains that half of the society’s founders included ministers, and that the adherence to religious doctrines and their insight into history’s impact on the present motivated the founders of the first historical society more than “provincial pride in local and ancestral achievement.” However, Boyd later describes how patriotism spurred public interest and funding and research.

The first of Franklin’s stated goals for local historical societies—collecting and preserving historical documents—proved both a major reason for the founding of local historical societies as well as a source of concern for later critics of historical societies. For instance, Franklin voices this concern in his book, believing that the historical society which devotes itself more to strictly local history than exploring such history’s national significance, “fails of the best part of its mission.”

Boyd links the founding of the historical society in Massachusetts and the subsequent rise of historical societies across the country to the “spirit of inquiry” which eighteenth century scholar Charles Thompson described in response to not only the founding of historical societies, but societies for scientific research such as the American Philosophical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

As Boyd explains, the Massachusetts Historical Society formed with humble beginnings, which he denoted as typical for most early historical societies. The original furnishings were sparse, says Boyd, and the organization could afford neither a salaried librarian nor even un-borrowed books.

Boyd states that a decade after the Massachusetts Historical Societies’ methods for historical research and preservation became more organized and sophisticated,

the New York Historical Society formed, following the blueprint established by the one in Massachusetts. New York’s society proved just as influential, as Boyd explains that its founders expanded the society’s broad interests to include fields like “natural history, science, religion, racial elements, and humanities.” Boyd describes this new structure as an “academy for the promotion of general knowledge,” complete with special committees for zoology, botany, and minerology. While many of these new departments in both New York and Massachusetts didn’t last (Massachusetts later sold its mineral collection), Boyd states that the New York Historical Society introduced “a broad and inclusive definition of history” which later societies echoed. The Lancaster Historical society website, for example, features published articles on a variety of topics including recreating historical garments from contributor Stephanie Celiberti. By the time leading historians founded the American Historical Association in 1886, Boyd explains that about 200 historical societies had been founded.

He explains that in 1904, the American Historical Association established an annual conference of the roughly 400 state and local societies to gather a report on how certain standards were being met.

Boyd ends his 1934 paper with a plea for a more formalized body of state and local historical societies, because all the American Historical Association could do was gather and report information.

According to Robert B. Townsend in the Autumn 2014 edition of History News magazine, that organization arrived in the form of The American Association for State and Local History (AASSLH). The first annual meeting, according to Townsend, convened in 1941 and addressed such issues as, “Raising the Standards of Historical Society Work,” and “a publication Program for Historical Societies.” Townsend lists Boyd, the then manuscripts curator of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, as one of the premiere architects of the AASLH’s split from the American Historical Association (AHA). Townsend states that the founding members of the AHA came mostly from the New England area and were shaped by the often those societies’ often outdated traditions, such as the Massachusetts Historical Society’s tendency to collect and publish materials about only a select few families.

Townsend credits Boyd’s writings for galvanizing historians to form a separate organization but notes that the realities of the Great Depression stalled their enthusiasm. Boyd and his fellow archivists, say Townsend, had broken away from the AHA in 1936, and by 1939 the firmer finances and organization of the societies made a formal break with the AHA possible.

Historian William T. Alderson Jr. writes in the April 1970 edition of Western Historical Quarterly that the AHA’s forming of the Conference of State and Local Historical Societies in 1904 proved possible partly because by the turn of the century, “nostalgia was overcoming the bitterness of the Civil War,” he says, “ and a sense of national destiny was overcoming the comic features of war with Spain.”

American state and local historical societies had therefore begun to solidify their societal purpose and how best to accomplish these goals. In the 1937 edition of the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Herbert A. Kellar writes that the “first and fundamental” function of a local historical society is the “the collection of historical materials related to the community.” His next important function is the preservation of those historical materials. Kellar’s list also includes the use, arrangement and listing of historical materials collected by the organization.

Although not directly associated with the AHA or the AASLH, the Lancaster County historical Society, formed in 1880, nonetheless meets all these requirements listed by Kellar. According to the society’s website, the Research Center is full of “genealogical and local materials, containing over 16,000 volumes and 2 million manuscripts including maps, microfilm, family files, and much more.”

Martha Abel, the director of the library and archives at the Lancaster Historical Society, explains during a site visit that her interest in working there began when she stopped in one time to see the exhibits, and she was struck by how the Society could bring history to light as well as to life.

Library assistant Marianne Heckles’ interest began much sooner, as she grew up loving history and earned a degree in history. She answers research requests from people in the community and helps organize the photo collection by scanning photos and adding them to the database. Abel helps show people how to find the research material or other information they are looking for. She also reads old documents in the archives to increase her understanding and better help her assist people. “We read the handwriting, so you don’t have to,” she explains.

Heckles answers research questions from people in the community, along with gathering photo collections and adding documents to the database. She says the most common requests she receives from people are for genealogical research and finding an ancestor’s gravestone.

According to Abel, most people who ask them for help are retired, seeking assistance with either family histories or property research. Both Abel and Heckles find the opportunities for discovery to be the most rewarding aspect of their jobs. Abel likes exploring “the many interesting facts about The County and people who lived here.”

Meanwhile, Heckles enjoys the thrill of finding a piece of information for someone, especially “if you’ve been looking for something for a long time and you find that thing for him.” Likewise, she states that one of the most challenging aspects of her job is instances of needing to help a researcher who “hit a brick wall.”

Abel also describes the difficulties of being able to find the desired information, though she doesn’t have as much contact with the public. For example, she explains that sometimes the relevant documents weren’t saved or were lost in a fire. Also, even available documents sometimes reference outdated terms such as comb-maker, huckster, and other objects/occupations that no longer exist in the vernacular.

Occurrences such as lost documents or outdated phrases can complicate her ability to archive or to make maps, which another one of her responsibilities. “We can’t answer all the questions.” she explains.

Nonetheless, Heckles describes a mostly positive public reaction to the services she and Abel provide. “I think in general we get a lot of positive feedback.”

As if on cue, a man exploring the building asks the two if the old clocks in the back room are donations. “Most are,” Able answers, “some to the historical society and some to the Heritage Center museum that used to be downtown. When that museum closed, we took over their collection.”

He seems satisfied with the response and makes his way back to the entrance.

Heckles explains that people come into the building almost daily to either ask for research help or to ask simple questions like that one.

Heckles feels that the Historical Society’s most important function is, “preserving history, especially local history.” Abel agrees, but adds another responsibility: “presenting history.”

A 2016 article by an AASLH contributor describes how local historical societies cannot sustain catering only to the retiring Boomer and Generation X populations. They therefore suggest catering to Generation Y (also known as Millennials). He/she states that, “exhibits will have to become less static, more digital.”

On that note, Heckles explains that one of the ways the Lancaster Historical Society has adapted to changes in society is to expand its online presence. She also said that because so much information is freely accessible online and that people are understanding more about history than they used to, that most people can answer “the easy questions” themselves. Therefore, the kinds of questions they ask are more complex and specific. Another issue is that the website doesn’t show most of the collections, which creates more confusion. Heckles states that she and others have undertaken a digital humanities project to strengthen the reach of the society’s educational initiatives. “You’d think history isn’t obsolete,” she says, “but the technology changes.”

Abel believes that most local historical societies function similarly to the Lancaster Historical Society.

Lancaster History Vice President Robin Sarrat supervises all fundraising and marketing, facilities management and work with exhibitions. She likes working with donors, because people who are interested in history make it possible for the society to achieve its goals. Sarrat explains that her key challenge is that their staff is “mid-size” at best, which forces them to creatively maximize their time and efforts—particularly under time constraints. “Organizations like ours,” she says, are always watching the budget to make sure they have enough resources.

In the 2012 edition of the magazine of the American Historical Association, Debbie Anne Doyle writes that small historical societies, “play an important role in in protecting and preserving the historical record and also interpret the past to the public.” She states that the future of local historical societies, “is entwined with the future of the historical profession.”

Doyle explains that the financial crisis at the end of the last decade left historical societies facing, “Draconian budget cuts, while competing for an ever-shrinking pool of private and government grant money.”

Sarratt notes that, “often we are pulling people from other departments, using staff creatively, and exploring paths to diversify income streams.”

Sarratt echoes Heckles’s sentiments about the all the positive response from the local community. “We get really great feedback from the public,” she says. “I think we have a reputation for good customer service and quality programs locally and regionally.”

For instance, Sarratt described encouraging responses to a recent exhibit on the 275 history of St. James Episcopal Church, as well as the African American Heritage Walking Tour.

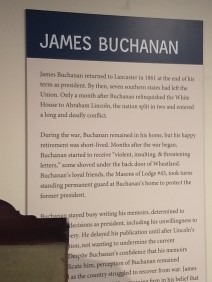

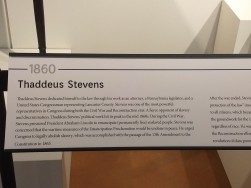

For Sarratt, the most important duty of he Lancaster Historical and is to, “protect and preserve the stories and histories of Lancaster County, and to educate the people about their history and teaching how to be good citizens.” She further describes that the last point about teaching civics exemplifies a change in the society’s goals over the past decade. Citing growing division in political discourse, she praised steps that the society has taken to better educate the public, such as establishing an education department. She believes that Lancaster history provides unique opportunities for such education, citing the progressive social politics of House Speaker Thaddeus Stevens, and the regressive social politics of President James Buchannan. Buchanan placated the South in the years leading up to the Civil War, while Stevens orchestrated and passed the thirteenth amendment which formally freed the African American slaves.

On November 22, 2019, The Lancaster County Historical Society opened a new exhibit, hosted a lecture, and launched a fundraiser. The Lancaster History website explains that the “Lancaster in the ‘60s” exhibit “examines the issues of conflict, resolution, and protest against the backdrop of four pivotal decades—the 1660’s 1760’s 1860’s, and 1960’s.” It also follows the stories of “ordinary Lancastrians who lived through extraordinary times.”

At 4 p.m—hours after the exhibit opening—Dr. Joshua A. Lunn, assistant professor of Civil War history at Eastern Kentucky University, gave a lecture on how James Buchannan and other Democrats, “influenced the populist politics of racial and gender backlash” which “still echo in modern day American politics.”

At twelve midnight on September 19, the society also launches The Extraordinary Give, a 24-hour digital donation drive.

Speaking before the openings, Sarratt explains that this busy period perfectly exemplifies, “how we use our staff creatively and with teamwork.” Two staffers lead the fundraiser both on-site and on-site, with backup support from two other teammates. “Another three of us,” says Sarratt, the Director of Education, the Assistant Curator, and the Meuseam Associate, will be “holding down the fort for the exhibition opening.”

The Director of Wheatland—James Buchanan’s historical home where the society bases its operations—would manage the lecture, with the help of other colleges assembled using a sign-up app. These colleagues would serve as hosts, parking assistants, and IT roles “to make sure the lecture comes off without a hitch.” The staff comprises 18 members in total.

In Sarratt’s view, “The key to our success is that while everyone has their own responsibilities and accountabilities, we are pretty adaptable and can fill multiple roles.”

Sarratt feels that the Lancaster County Historical meets most of Franklin’s stated functions for a local historical However, she felt that Franklin’s goal of keeping alive “a patriotic regard for local history,” serves little purpose to the Lancaster Society, which concerns itself far more with education than promoting local pride: a function she reserves for larger historical societies with better funds and broader scopes.

Source list

Interviews:

Martha Abel, director of the library and archives Lancaster Historical Society. Face-to-face interview, November 9 2019

martha.tyzenhouse@lancasterhistory.org

Marianne Heckles, library assistant at the Lancaster Historical Society Face-to-face interview, November 9 2019

ne.heckles@lancasterhistory.org>

Robin Sarratt, Vice President of the Lancaster historical Society Face-to-face interview, November 19, 2019

robin.sarratt@lancasterhistory.org

Print Sources:

Doyle, Debbie Annie. “The Future of Local Historical Societies.” The News Magazine of the American Historical Association, 2012. https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/december-2012/the-future-of-local-historical-societies

Boyd, Julian. “State and Local Historical Societies in the United States.’.” The American Historical Review, vol. 40, no. 1, Oct. 1934, pp. 10–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1838672?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contentsJ. Franklin (John Franklin), “The Functions of State And Local Historical Societies.” [p 53-59], 1897.https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=loc.ark:/13960/t6d229k6v&view=1up&seq=1

AASLH Contributing Author. “Historical Societies and the March of Time.” Nov. 14, 2016. Accessed at https://aaslh.org/historical-societies-and-the-march-of-time/ November 17 2019

Alderson, William T. “The American Association for State and Local History.” Western Historical Quarterly Vol. 1, No. 2 (Apr., 1970). Accessed at https://www.jstor.org/stable/967859?seq=1 November 17 2019

Townsend, Robert B. “AASLH and the break with the AHA.” B. History News. Autumn2014, Vol. 69 Issue 4, p 23-25. Accessed at http://eds.a.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=578a321f-fd5d-4e17-82b0-97812f6a31de%40sdc-v-sessmgr03 November 17, 2019

Kellar, Herbert A. “The Functions of a Local Historical Society.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society Vol 29, issue 4 Jan 1937. Accessed at https://www.jstor.org/stable/40187464?seq=1 November 17, 2019